I want to be Phil Douglis when I grow up.

By John Gerstner, CEO, Communitelligence

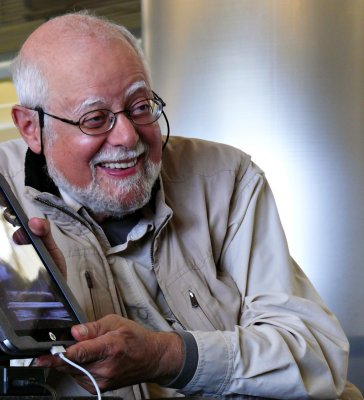

Here’s Phil, 80 years old, enjoying his “retirement” as a globetrotting photographer. He just got back from Bolivia. According to his travel map, he has now visited 38 percent of the countries in the world.

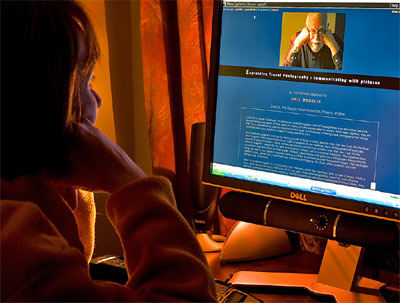

Since 2003, he’s been posting the output from these trips in a huge collection of galleries titled “Expressive Travel Photography and Travel Photojournalism: Communicating with Pictures,” which amounts to a giant “cyber-book” on photographic expression. It is undoubtedly the largest and most comprehensive instructional resource on visual literacy on the Web, and it’s all free.

In 10 years, the site grown to include 90 galleries containing 4,000 stunning images that have drawn more than nine million views and 20,000 comments. Phil has painstakingly written commentary on each image, and replies to most comments from viewers.

If there has ever truly been a labor of love, this is it. Phil’s offers this instructive website as a service, his way of giving something back to an art form that provided his livelihood from 1971 to the present day. As director of the Douglis Visual Workshops, he trained more than 10,000 corporate communicators in visual literacy through his nationwide series of workshops, and while he has long since retired from the workshop trail, he still offers one-on-one tutorial workshops in digital imaging and photographic communication at his Phoenix, Arizona, home.

It was at one of his Chicago workshops that I first met Phil back in the 1990s. I share a passion for expressive photography and that’s kept us in contact ever since. (P.S. Someday I want to go on a shoot with Phil in Arizona),

About his monumental collection of free images published in his free cyber-book, his motive is simple and pure: to help viewers learn how to better express their own photographic ideas … “particularly how to interpret, rather than just describe, what we see before us.”

I believe this purity of motive combined with his enduring passion to go beyond creating literal travel snapshots, even artful ones, to capturing images that interpret the things seen infuses his work with meaning. And that’s his goal.

“I call these pictures “expressive” images,” Phil says. “They are images made for public, rather than private meanings. Expressive photography, like all art, offers universal, and often metaphorical, statements.” In other words, Phil creates images that go beyond what the eyes can see. They are a joy to experience. See for yourself.

“I will never really retire,” says Phil. “At 80 I feel as energetic and enthusiastic as I did at 50, and much more knowledgeable, too. Digital photography has changed my life, to be sure.”

I recently asked Phil if he would answer some of the many questions I have about his lifelong work as a photographer and teacher. He generously answered 10 , and if his answers spark a question from you, add it as a comment and I’ll bet he’ll reply. Now meet Phil Douglis, the consumate communicator with a camera.

What country would you like to return to photograph, and why?

-

Gentoo Rookery, Paradise Bay, Antarctica, 2004

I’ve made photographs in more than 75 countries over the past forty years, and each of them has offered a range of substantive content. The one “country” that I would most like to photograph again is not even a country. It is an entire continent — Antarctica. When I last visited there ten years ago, I was aboard an ocean liner. The spectacular scenery allowed me to make evocative photographs from the deck of the ship. However, due to weather related conditions, we only were able to spend a single hour on shore during our three-day visit. During that hour, I wandered among thousands of penguins, and photographed them in their nesting colonies. We also were able to take advantage of beautiful light for nearly 24 hours a day. Antarctica remains the most unspoiled place on earth. It is a wonder that it still remains pristine. How long can it remain so? It remains a dream of mine to be able to return someday to interpret Antarctic in greater visual depth.

What is your absolute favorite photograph you’ve made? Why?

There are more than 5,000 images in my instructional galleries. This one remains my favorite — a spontaneous moment of pleasure caught in within a Moroccan environment. I was walking through the souks of Marrakesh when I saw a shaft of sunlight illuminating an ancient wall within an archway at the end of a dark and narrow street. I heard distant voices of children at play, getting closer and closer. I framed the shot and waited, and within a few seconds a kid came flying into the arch. I squeezed the shutter button and caught him just as he landed. The magic of photography will always keep him in this spot, framed in fiery red, a symbol of youthful exuberance. The arch constrains motion as the shutter of the camera, catching the scene within a specific – and decisive — moment in time. The spatial constraints of the arch create the tension that holds this image together. Why is it my favorite? It stands the test of time. I made this image eight years ago, and it never fails to stir my emotions and my imagination.

What three things would you recommend to amateur photographers that would help make their images substantially better?

I am often asked that question. I answer it in the introduction to my instructional galleries at pBase.

Here is what I said:

“Expressive photography is based upon the three principles I demonstrate in the first three galleries on this website: Abstraction, Incongruity, and Human Values.

Abstraction removes literal, descriptive clutter and hones an image down to its essence and encourages unlimited thinking. Incongruity presents elements that seem to be at odds with their context and creates contrasts and juxtapositions that stimulate both the emotions and the imagination. Human values convey the emotions, beliefs, traditions and knowledge that we understand and share as humans. I suggest that anyone using this website as a learning tool, study these three galleries before going on to the rest of them.”

I believe that human values hold the key to expressive photography. They stand at the base of a triangle of principles upon which I build my images. Abstraction runs up one side of this triangle, incongruity the other, and human values supports both of them. Without this triangle, expression does not occur, and without human values, the triangle does not stand, because abstraction and incongruity will have no anchor.

Once we know the humane point we are trying to express to our viewers, we can then consider how to abstract the image to reveal its essence, as well as how to bring either perceptual incongruity or subject incongruity into play. And then we can go on to fine-tune our image with color, mood, atmosphere, composition, and best make our decisions in controlling light, perspective, and moments in time.

These options are not Phil’s “rules or laws of expressive photography.” This is simply how I choose to understand and use the language of photographic expression, a language that, above all, must be a human, rather a technical, language.”

Is it normal to shoot 15,000 images to wind up with 100 that you are happy with?

Keep in mind that when I shoot as many as 15,000 images, they would be spread over a month long shoot. That comes to about 500 shots a day. I usually shoot for about three to four hours a day (I used to shoot for six or seven, but now that I am 80 years old, the legs don’t last as long as they used to) so I am essentially shooting about 160 images an hour. I usually do not shoot a subject just once. I usually make many exposures of a single subject from various positions and at different moments. I call this “working an image” until I either get what I want, or fail to do so. At the end of those three hours, I have usually made 500 pictures. I spend about three hours working on those images on my laptop computer. I try to whittle that number down to 10 or so keepers for each day of shooting. At the end of a month long trip, I usually come home with about 300 keepers, and I will try to use about a third of them in my teaching galleries. (If my photo trip is a shorter one, my overall picture counts will be proportionally smaller.)

Your work is obviously a labor of love. You give of your techniques and wisdom so freely on your two websites. Do you still do photo workshops?

I gave my last photo workshop in 2006. I am essentially “retired,” but I will still work with individual photographers and communicators in a one-on-tutorial format. They travel to my home in Phoenix to work with me for one to four days. We shoot together, and I try to help them change the way they see as a photographer or as a photo-editor, no matter what their level of skill might be. Much of my time is spent making pictures for my instructional website – through my travels, I am constantly refining my own photographic approach. I pass on whatever I learn to my on-line students. I now have more than 5,000 images on-line, and I explain how and why I made each of those images. I’ve had more than nine million hits on my site so far, and over 11,000 people have left comments and questions below my photographs. I have responded to every one of them. As you can see, such an interactive website keeps me very busy. I am often asked why I provide such an educational resource at no charge. My answer is simple. Photography has given me my livelihood and my pleasure for more than 50 years. In retirement, I want to give something back to photography, and this is how I’m doing it.

Of your connection to photography and publishing it on the web, what aspect of it gives you the most reward?

The answer to that question is very simple. I want to help photographers at all levels learn how to express ideas with their images instead of merely describing the appearance of things and people. That is what I’ve done in my workshops, my tutorials, and through my columns for IABC and my instructional website. It is extremely gratifying to know that my ideas can valuable to other creative people. I also find that the more I photograph and teach, the more I continue learn about photographic expression. And that, too, is quite rewarding.

What is the mental mindset you try to have when you are on the ground making photographs.

On the ground? John, if were to shoot on the ground, I would need a permanent assistant to lift me to my feet after every shot. At age 80, the knees no longer allow me such luxuries as ground level shooting. (Of course I have always had a flip out viewfinder on my camera, so I can simply lower the camera between my knees and get the same effect without ever having to go to the ground.)

Of course you did not ask that question in literal terms. You are really asking me how I think when I am out shooting, right? As I shoot, I keep reminding myself to “see” instead of just looking for something to shoot. I am always thinking about how things relate to each other in space and time, and how those relationships change as I move my position. I think about how colors work together or at odds. I try to study the interplay of light and shadow, looking for ways to abstract an image and find an essence, instead of just putting a subject into my frame and pushing the shutter button. And ultimately, I am always searching for incongruities in size, role, attitude, and appearance. In other words, my mental mindset is essentially that of an explorer in search of meaning.

How much encounter do you have with the locals? Do you often engage them in conversation, or are you the man behind the camera, silently moving through their environment?

Before go on a shoot, I try to research my subject so that I have at least some idea of social and cultural norms. The more I know in advance, the more knowledge I can bring to a given situation. I have often met some of my on-line students in far away places, and since they are all photographers themselves, I am able to get a look at a culture or society from the inside, rather than as an outsider. In some cases, I engage the services of a guide, who not only understands my mission, but also speaks the local language, and can sense if people are reacting to my camera in a negative manner. My guides also “watch my back” in crowded urban areas, where personal safety can sometimes be an issue. As for how I interact with my subjects, I try to avoid posed pictures, because they usually end up as smiling or self-conscious photographs of people having their pictures taken. I never pay subjects either. That kind of behavior encourages some locals to see touring photographers as a commercial opportunity. Instead I prefer spontaneity, reality, and honesty in my imagery. I often use a long telephoto lens, so that my subject most likely will not notice me. If I am using a wide-angle lens, I will move in on my subject and look either to the left, right, above or below, but never directly at the subject. The person I am photographing often thinks I am photographing something else, but my wide-angle lens includes both the environment and the subject within its frame. Every now and then I will make a portrait head on. I will smile and nod, point to my camera, and if there is no objection, I will make the picture. If the person is smiling back, I usually discard the image. But sometimes a person will simply stare into my lens, offering me a glimpse of their soul. I keep such pictures.

The age of a photographer playing the role of the “fly on the wall,” has largely passed. Cell phones have made everyone into a potential photographer. Every now and then, when I am photographing people, someone will spontaneously make a picture of me as well. We then can share our images with each other, and at least for a few moments, share an interactive experience with each other.

How do you prep for trip? Do you study its history, customs, etc. or do you arrive with fresh eyes, trusting that you will discover the essence of a place without being steeped in it beforehand?

Travel research is very easy in the age of the Internet. I can read extensively about a country on Wikipedia or Trip Advisor. I search the photo-sharing sites such as Flickr, Smugmug, and pbase for galleries on the country or city I will be shooting. I look for evocative imagery and take notes on where such images were made. Once I arrive in a city or country, I not only visit the places I know about. I try to go into neighborhoods where tourism is rare. Many of my strongest images have come out of such places, because they have not yet been commercialized or gentrified. And finally, as I’ve noted in answers to your other questions, I rely on either my local contacts, or on a professional guide, who may be able to take me to places where I can have the best chance of finding the essence of city, country, or culture.

You must be an excellent world traveler. Any thoughts on that aspect of what you do.

I try to travel to places where “travel business” does not yet exist. This is getting more difficult to do as places become more commercialized. However there are still certain parts of countries without extensive tourism infrastructure in place. For example, in Vietnam, after dutifully taking in the major cities and their tourist “sites,” we hired a driver and guide to take us into the small towns of the Mekong Delta area for a week. We stayed in local hotels, ate in local restaurants, and were even invited to attend a local wedding and then visit the homes of some of the guests. During my recent trip to Bolivia, we stayed for three weeks in a town that most tourists only spend one or two nights visiting.

Now and then, I have been able to stay and shot in one town or city for an extended time. This makes it possible for me to photograph in local neighborhoods, as well as in villages on the outskirts of town that rarely host foreign visitors. I can return to certain places at different times of day or night, and see them in fresh ways. I used to take tours for the sake of economy and expediency, but found that most of them visit places during the worst times to photograph – between ten in morning and two in the afternoon when the sun is high and the shadows are harsh. During the best light of the day, just after dawn and just before dusk, packaged tours are usually devoted to having breakfast and dinner. I have ceased taking them altogether and try to travel either independently or else take tours that stay in places over a longer period.

I also find that overseas travel is now more difficult for me because of ever more crowded flights and my advancing age. I have narrowed my focus to shorter flights in the Western hemisphere that do not involve long ocean crossings. It is easier to break up a long flight with an overnight stay somewhere at the midpoint of the journey than sit for ten, twelve or fourteen hours crunched in the back of a plane.

I prefer to shoot on a travel schedule that best suits my needs as a photographer. I try to have an early light breakfast and shoot from seven to nine in the morning. I will edit my pictures on my laptop and rest a bit between ten and three when the light is at its worst. I like to sometimes go back and shoot some more between three and sunset if the subject and the mood warrants. If I am traveling from one place to another, I will shoot early, travel during the middle of the day, shoot in the late afternoon when I get to where am going, and then edit my pictures in the evening.

I always try to download to my laptop all of my pictures from my memory card immediately following each shooting session. I reformat my card every time I download, and always start with a clean memory card the next day. And I always delete my rejects – I never let them hang around to clutter my life. I come back from a trip with only my keepers in hand.

0 responses on "Phil Douglis: Photographing What Eyes Can't See"